The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock

"S’io credesse che mia risposta fosse

A persona che mai tornasse al mondo,

Questa fiamma staria senza piu scosse.

Ma percioche giammai di questo fondo

Non torno vivo alcun, s’i’odo il vero,

Senza tema d’infamia ti rispondo."

- Lungarno: Il viaggio a Tartaro con Virgilio

Let us go then, you and I,

When the evening is spread out against the sky

Like a patient etherized upon a table;

Let us go, through certain half-deserted streets,

The muttering retreats

Of restless nights in one-night cheap hotels

And sawdust restaurants with oyster-shells:

Streets that follow like a tedious argument

Of insidious intent

To lead you to an overwhelming question ...

Oh, do not ask, “What is it?”

Let us go and make our visit.

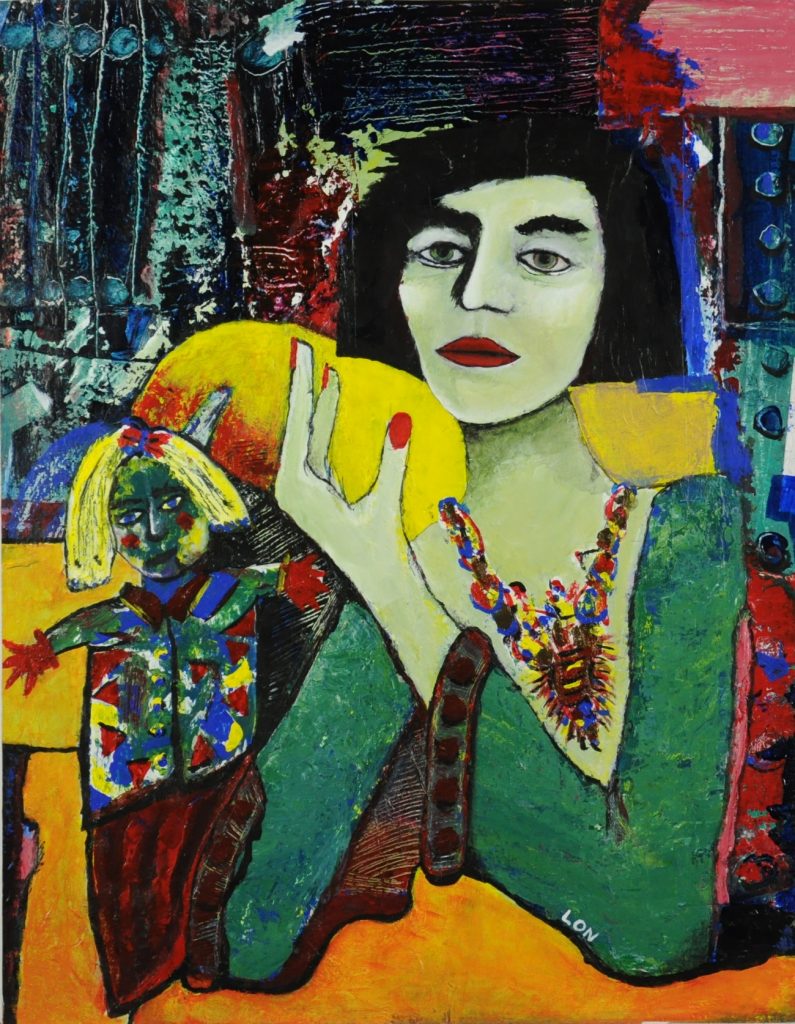

In the room the women come and go

Talking of Michelangelo.

The yellow fog that rubs its back upon the window-panes,

The yellow smoke that rubs its muzzle on the window-panes,

Licked its tongue into the corners of the evening,

Lingered upon the pools that stand in drains,

Let fall upon its back the soot that falls from chimneys,

Slipped by the terrace, made a sudden leap,

And seeing that it was a soft October night,

Curled once about the house, and fell asleep.

And indeed there will be time

For the yellow smoke that slides along the street,

Rubbing its back upon the window-panes;

There will be time, there will be time

To prepare a face to meet the faces that you meet;

There will be time to murder and create,

And time for all the works and days of hands

That lift and drop a question on your plate;

Time for you and time for me,

And time yet for a hundred indecisions,

And for a hundred visions and revisions,

Before the taking of a toast and tea.

In the room the women come and go

Talking of Michelangelo.

And indeed there will be time

To wonder, “Do I dare?” and, “Do I dare?”

Time to turn back and descend the stair,

With a bald spot in the middle of my hair —

(They will say: “How his hair is growing thin!”)

My morning coat, my collar mounting firmly to the chin,

My necktie rich and modest, but asserted by a simple pin —

(They will say: “But how his arms and legs are thin!”)

Do I dare

Disturb the universe?

In a minute there is time

For decisions and revisions which a minute will reverse.

For I have known them all already, known them all:

Have known the evenings, mornings, afternoons,

I have measured out my life with coffee spoons;

I know the voices dying with a dying fall

Beneath the music from a farther room.

So how should I presume?

And I have known the eyes already, known them all—

The eyes that fix you in a formulated phrase,

And when I am formulated, sprawling on a pin,

When I am pinned and wriggling on the wall,

Then how should I begin

To spit out all the butt-ends of my days and ways?

And how should I presume?

And I have known the arms already, known them all—

Arms that are braceleted and white and bare

(But in the lamplight, downed with light brown hair!)

Is it perfume from a dress

That makes me so digress?

Arms that lie along a table, or wrap about a shawl.

And should I then presume?

And how should I begin?

Shall I say, I have gone at dusk through narrow streets

And watched the smoke that rises from the pipes

Of lonely men in shirt-sleeves, leaning out of windows? ...

I should have been a pair of ragged claws

Scuttling across the floors of silent seas.

And the afternoon, the evening, sleeps so peacefully!

Smoothed by long fingers,

Asleep ... tired ... or it malingers,

Stretched on the floor, here beside you and me.

Should I, after tea and cakes and ices,

Have the strength to force the moment to its crisis?

But though I have wept and fasted, wept and prayed,

Though I have seen my head (grown slightly bald) brought in upon a platter,

I am no prophet — and here’s no great matter;

I have seen the moment of my greatness flicker,

And I have seen the eternal Footman hold my coat, and snicker,

And in short, I was afraid.

And would it have been worth it, after all,

After the cups, the marmalade, the tea,

Among the porcelain, among some talk of you and me,

Would it have been worth while,

To have bitten off the matter with a smile,

To have squeezed the universe into a ball

To roll it towards some overwhelming question,

To say: “I am Lazarus, come from the dead,

Come back to tell you all, I shall tell you all”—

If one, settling a pillow by her head

Should say: “That is not what I meant at all;

That is not it, at all.”

And would it have been worth it, after all,

Would it have been worth while,

After the sunsets and the dooryards and the sprinkled streets,

After the novels, after the teacups, after the skirts that trail along the floor—

And this, and so much more?—

It is impossible to say just what I mean!

But as if a magic lantern threw the nerves in patterns on a screen:

Would it have been worth while

If one, settling a pillow or throwing off a shawl,

And turning toward the window, should say:

“That is not it at all,

That is not what I meant, at all.”

No! I am not Prince Hamlet, nor was meant to be;

Am an attendant lord, one that will do

To swell a progress, start a scene or two,

Advise the prince; no doubt, an easy tool,

Deferential, glad to be of use,

Politic, cautious, and meticulous;

Full of high sentence, but a bit obtuse;

At times, indeed, almost ridiculous—

Almost, at times, the Fool.

I grow old ... I grow old ...

I shall wear the bottoms of my trousers rolled.

Shall I part my hair behind? Do I dare to eat a peach?

I shall wear white flannel trousers, and walk upon the beach.

I have heard the mermaids singing, each to each.

I do not think that they will sing to me.

I have seen them riding seaward on the waves

Combing the white hair of the waves blown back

When the wind blows the water white and black.

We have lingered in the chambers of the sea

By sea-girls wreathed with seaweed red and brown

Till human voices wake us, and we drown.

Courtship Song of J. Arthur Prufrock

“If I thought what I say to you would go

to anybody bound for worldly light,

this brand would stop pulsating and fall still.

But nobody’s got out of our abyss

living, if I’m told truth; and so, I shall

inform you, unafraid of infamy”.

- 'To Tartarus with Virgil'

OK Vamos, you and I,

Now that dusk is sprawling on its backdrop sky,

Aping an invalid whom chloroform’s put down;

Vamos, through various not-that-busy ways,

Susurrating slinkaways,

Insomniac nights in short-stay low-class inns

And sawdust snackbars flush with crayfish skins:

Ways dogging you with boring how-d’you-do

Cunningly bugging you

To bring you a tyrannical conundrum…

Oh, do not ask, “What is it?”

Just carry out our visit.

Backward and forward trips posh totty

Talking of Italy’s Buonarotti.

That sallow fog that rubs its back on window-glass,

That sallow smog that rubs its jaws on window-glass,

Licking its lingual prong into nooks of dusk,

Hanging round pools that stand in drains,

Took on its back soot-falls from filthy stacks,

Slid by a run of doors, did a quick jump past a gap,

Saw that it was a soft autumnal night,

Wound simply round a flat, took a nap.

And this won’t fail: an opportunity

For sallow smog that slips down murky ways

Rubbing its back, again, on window-glass;

An opportunity, an opportunity,

To fix a phiz fit to quiz any phiz;

To go all homicidal, or to bring

Good things to birth; for works and days of hands

That lift and drop conundrums in your lap;

Your opportunity, my opportunity,

To wallow in a thousand doubts of mind,

A thousand visions won, a thousand lost,

Partaking finally of Whittard’s Black, and toast.

Backward and forward trips posh totty

Talking of Italy’s Buonarotti.

And this won’t fail: an opportunity

To think: “Am I so bold? Am I so bold?”

To turn again, go down that stair

With a bald spot as hub-cap of my hair,

(Folk will say: “How his hair is growing thin!”)

My morning coat, my collar mounting firmly to my chin,

My cravat rich and unassuming, with a thrifty pin—

(Folk will say: “Just look at his limbs, how thin!”)

Am I so bold

As to carry out a cosmic discommoding?

In an instant I can find

Ultimatums in my mind, with an option of swift unloading.

For I know it all, right now, oh I know it all:

Know of dusks, of mornings and long-past-noons,

Counting out my days with mocca-spoons;

Know of small-talk dying with a dying fall

Which a distant music laid out cold.

So how should I wax bold?

And I know of orbs of sight, I know it all,

Orbs that fix you in a formula, a way of saying,

And caught in that formula I’d sprawl, stuck fast

On a pin and wriggling against a wall:

Say, how should I start

Spitting out ciggy-butts of my days and ways?

And how should I wax bold?

And I know of arms, right now, oh I do know it all:

Brightly dight with bling, skin unclad, lily-fair

(Though in lamplight, downy with light brown hair).

Is it a fragrant frock

Brings on my logic-block?

Arms laid along a board, or wrapping round a shawl.

And am I to wax bold?

And how should I start?

Shall I talk of going at dusk through narrow ways

Watching vapour curling up from solitary souls

Smoking with no coats on, hanging out of windows?...

What if I wasn’t I, but two tatty claws

Scuttling on salt floods’ tranquil floors…

. . . . . . .

And noon is napping placidly, and dusk is too!

Stroking of long digits:

Laid out… lassitudinous… or it fidgits,

Lying long on this floor, by yours truly, and you.

Should I, upon a cuppa char, a pastry, a cassata,

Push this occasion into ultimata?

With orbs in flood, and off my food, my orison was said:

I saw my balding topknot on a tundish, most unkind,

But I’m not Giambattista and I don’t much mind;

I saw my opportunity of triumph slip,

I saw God’s Footman hold my coat, and curl his lip

And in short, I was afraid.

If I had, was it actually worth it, anyway,

Following two cuppas and a fruit-slop on a spoon,

Among china crocks and a chat about us two,

Was it actually worth it, to do,

If I bit off such a topic with a grin,

If I shrank God’s cosmos into a ball

To roll it towards a gigantic inquiry,

To say: “I am Lazarus, I’m an apparition,

Giving you my story, I’m giving you it all” –

If a lady, comfortably placing a cushion,

Should say: “That is not what I had in mind at all;

That is not it, at all.”

Was it actually worth it, anyway,

If I had, was it actually worth it?

What with nightfalls, dooryards and civic hosings-down,

Works of fiction, cups of Lipton, a trailing skirt or gown,

And that, and much on top of that? -

I can’t possibly say what I’m driving at!

But as if a magic gizmo put my ganglia in graphs upon a wall:

If I had, was it actually worth it,

If a lady took a cushion or was throwing off a shawl,

And turning toward a window, should say:

“That is not it, at all,

That is not what I had in mind at all.”

No! I’m not that Danish royal, not cut out for it;

Just an auxiliary lord, who’ll do

To bulk out a walkabout, start an act or two,

Advising HRH; no doubt, a handy tool,

Knowing my station, glad if I do good,

Politic, cautious, acting as I should,

Full of high opinion, but as thick as wood;

Now and again, almost ridiculous –

Almost, in fact, his Fool.

I grow old … I grow old …

I’ll roll up my turn-ups, I’ll turn out bold.

Shall I part my hair abaft? Might I munch a mango, coolly?

I shall walk damp sand in plus-fours, tint of lily.

I saw nymphs with fishtails, singing songs, mutually.

I do not think that choir will sing for yours truly.

I saw nymphs riding on salt surf to far horizons,

Combing foaming hair of salt surf blown back

By wind that blows on surf both milky and black.

You and I may tarry in old Triton’s halls

With nymphs wrapt in salt-grass crimson and brown

Till human music warms us and charms us to drown.